Project Description

Master Classes are deep dives into venture creation by MIT ecosystem thought leaders. Browse all Master Classes Here.

This master class is based on notes taken during a workshop in 2020 by Jason Jay, Senior Lecturer, together with AJ Perez, entrepreneur and Ph.D. candidate at MIT.

Overview

This workshop is about impact entrepreneurship. It addresses some nuances involved in designing, pitching, and building enterprises that explicitly seek a positive impact in the world. It also recognizes that most enterprises have some potential for positive impact that entrepreneurs can amplify to help secure the best talent, investors, and customers. The workshop is relevant whether you are impacting society (health, education), the environment (carbon, water, waste, soil), the economy (financial inclusion, fair trade, labor standards), politics, or other public interest domain.

Six Axioms of innovating for impact

It’s a very enlivening thing to try to create an enterprise that makes the world better and to do well commercially and financially while doing good in the world. That’s a big promise. But it is a little tricky, because we often don’t make some very important distinctions.

Let’s look at the six axioms in innovating for impact.

- Passion <> Problem

- Public problem <> Private problem

- Stakeholder <> Customer

- (Social) Value creation <> Value capture

- Intention <> Impact

- Sustainability<> Technological Innovation

Passion is not equal to problem. A public problem is not equal to a private problem. A stakeholder is not equal to a customer. Social value creation is not equal to value capture. Intention is not equal to impact. Sustainability or impact oriented innovation is not just about technological innovation.

In this master class, we will be looking at the first three axioms to build towards pitching the problem. This is an integral part of being able to be effective in pitching your enterprise. You need to make it clear about why people should even care. What is the problem that you’re trying to solve in the world? And why does this add up to something that’s worth investing in, that’s worth coming to work for, that’s worth joining the team, or that’s worth being a customer?

The first axiom: Passion <> Problem

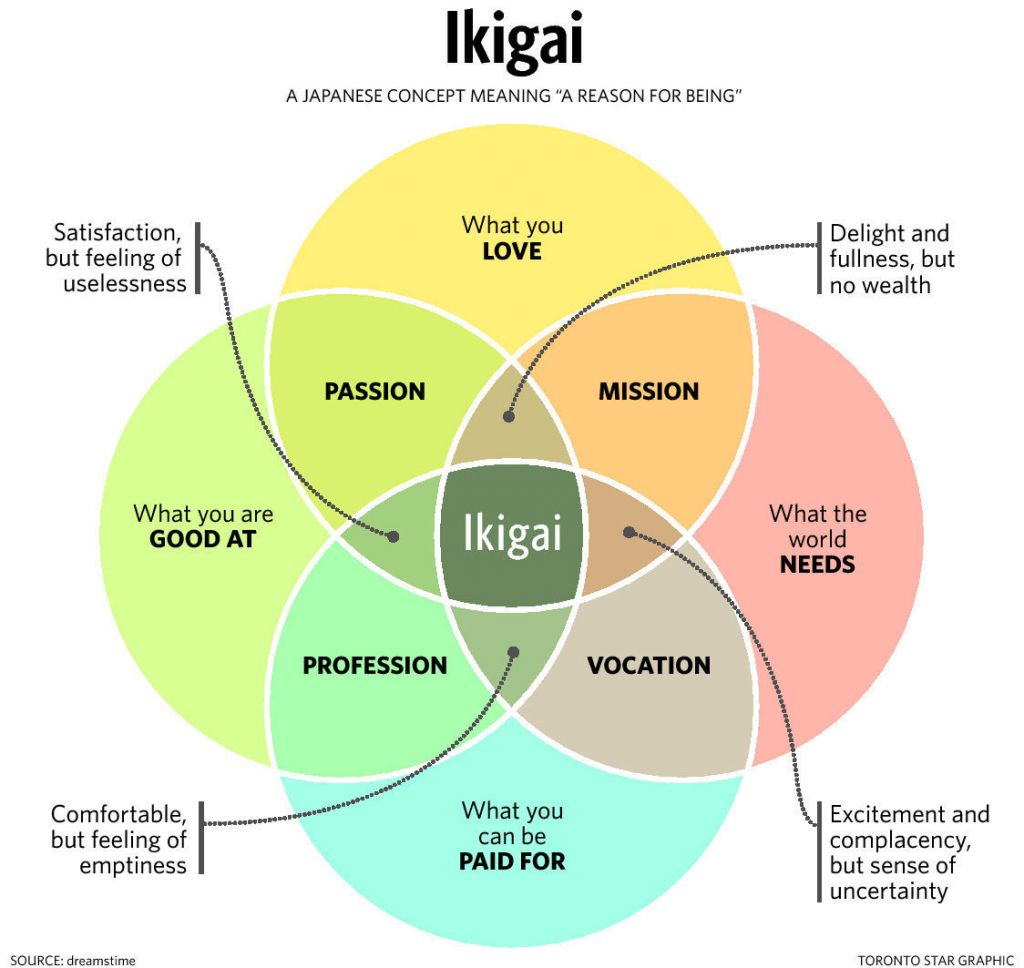

Following is a Venn diagram that is helpful for talking about innovating for impact. This concept is called Ikigai – a Japanese concept meaning “A reason for being”.

A really compelling part of purpose-driven work is about finding some kind of an intersection between the following:

- What we love to do

- What we’re good at, what we are skilled at and have distinctive competency

- What the world needs, what are important problems to solve in the world

- What we can be paid for, what will actually be able to draw in revenue because it’s worth something financial to somebody.

What inspires people, and why people love to come to the demo days and listen to pitches to be part of entrepreneurial communities, and to be investors is because we are striving for that Ikigai. No one’s going to give me a job where I’m going to be able to find that perfect sweet spot. So I’m going to create it myself.

And investors feel the same way. If I can go out there and really get involved in an enterprise, I might find some way to do something really fun, put my own skills to use, and solve some important problems in the world.

Ikigai is a journey and not a solution state. It’s something that you’re going to be constantly doing throughout your life. Imagine a spiral on this picture where each step that you take in your professional life is maybe a nudge in a direction that gets you a little bit closer to the center, giving you a chance to explore these different facets.

Now the important thing here is that while we’re looking for this kind of integration, the first step is actually to tease these things apart carefully.

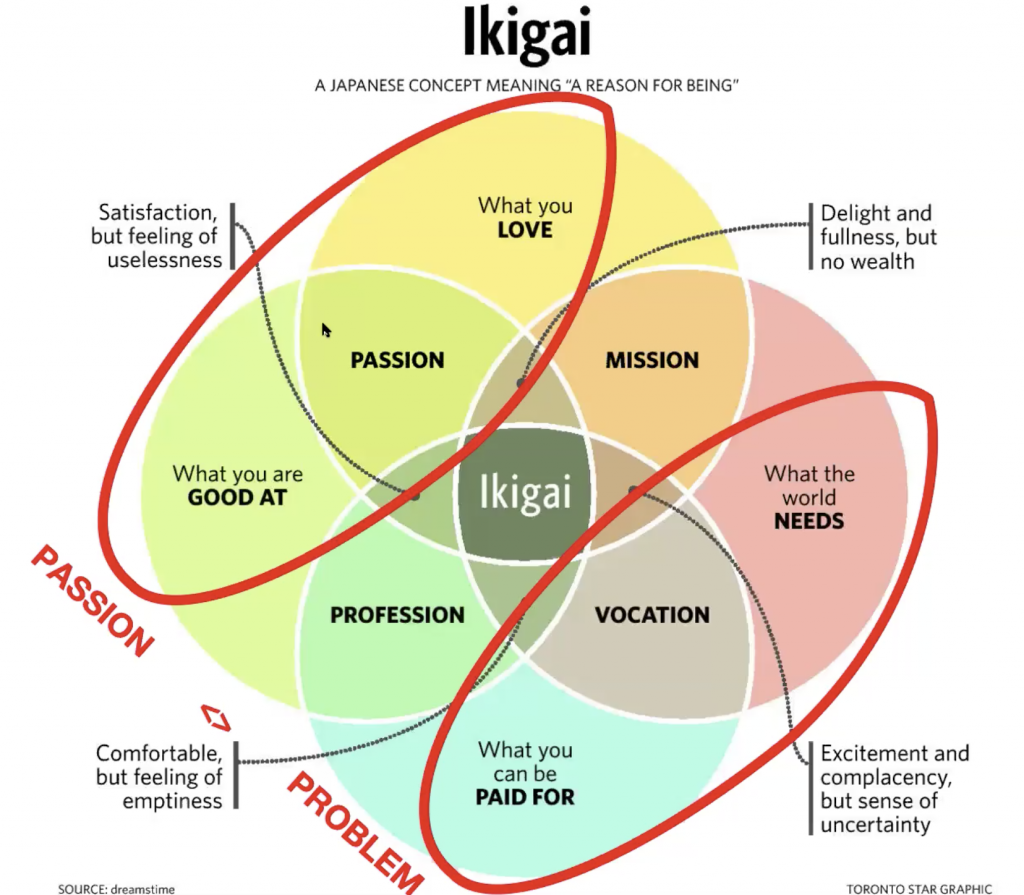

Spoiler Alert Case: Passion for sustainability versus problem of food waste

We’re going to be making use of a particular case example called Spoiler Alert. Spoiler Alert is a group that was founded by two MIT Sloan students when they were here. Ricky Ashenfelter and Emily Malina were 2016 MBA alumni. Ricky and Emily came here with an interest in sustainability topics. Ricky had been working for a carbon accounting firm. Emily had been working in enterprise software. They were both good at what they did – consulting and software. But they had this latent interest and passion for topics around the environment and around sustainability.

So they had real interest and history in this terrain, but when they were trying to come up with a business that’s going to draw in investment capital and revenue and solve important problems in the world, they had to tease out that passion side of things from what’s a worthy problem to solve.

You need to learn to communicate what is the problem that we’re trying to solve, what are the problems to solve that the world needs – and that you can be paid for. You need to do it in a way that’s not just interesting and logical to yourselves given your passion, but that anyone in your audience can relate to, especially among your prospective employees, investors and prospective customers.

There will be a lot of times where things might be self-evident to you. But it may not be obvious to everybody to everyone else. And so being able to articulate those problem statements is extremely important.

The second axiom: Public problem <> Private problem

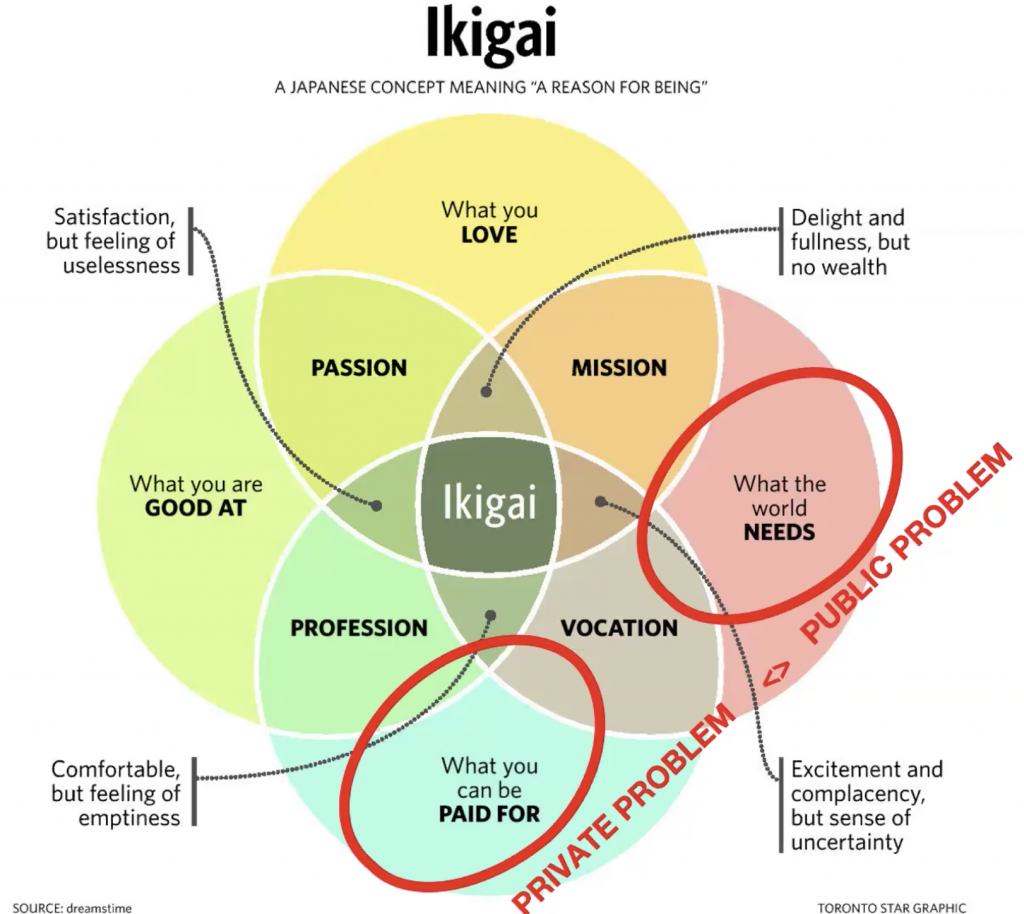

Once you start to do that, you come to the second distinction: The public problem versus the private problem.

Ikigai: A reason for being

This distinction is nicely mapped on the following picture, which is the distinction between a public problem – something that the world needs or that communities need or that our country needs, or that we as citizens understand the need for… versus a private problem – something that is owned by a specific individual who will pay you to solve that problem for them.

Private problem alone is not enough

This is one of the biggest challenges in innovating for impact. If you’ve been really deep into the empathy part of the design thinking process, you really understand your customers. You understand their private problem really well, you know they’ll pay you for it. Sometimes, you really have to put the energy into understanding how this has wider relevance. You need to learn how to strike a wider cord and connect it to some sort of a public problem. Some people may need to just do more work on this side of the picture.

Public problem alone is not enough

Conversely, some people go after their innovation because they’re trying to solve a public problem. For example, they may be trying to go after climate change, inequality or poverty. But they haven’t quite figured out who a paying customer is going to be for this solution. For example, we know that satellite imagery is going to be relevant to being able to solve deforestation, because it can show you where deforestation is happening. But who’s the person who’s going to pay you for that technology, for that data, whose private problem does that solve? That is a totally different question.

Teasing things apart for Spoiler Alert

It is worth teasing these things apart, articulating them each on their own terms, and then fastening them together into a narrative that really combines both.

In many of Spoiler Alert’s presentations, they’ll start off with the big picture: “40% of the food that we grow in the world doesn’t end up feeding people”. It is wasted in some way or another. It goes to waste on the farms, or it goes to waste in the supply chain, or it goes to waste as surplus inventory in stores or distributors.

If we talk about food waste, whose problem is this?

On the one hand we can look at food waste as a public problem. The environmental impact of growing that food and throwing it away is something we all bear. The missed opportunity to feed people and address hunger is a public problem. As a collection of citizens, we should deal with, understand and try to improve things.

If we look more closely, food waste is a supply chain and food system issue. There are a bunch of different actors. There are the suppliers. There are the consumers where people are demanding variety. We have to supply that variety, but sometimes there is surplus inventory. So the waste is something that arises out of an interaction of a bunch of different players. And many of us could look at this and say, oh, we probably all have a stake in this.

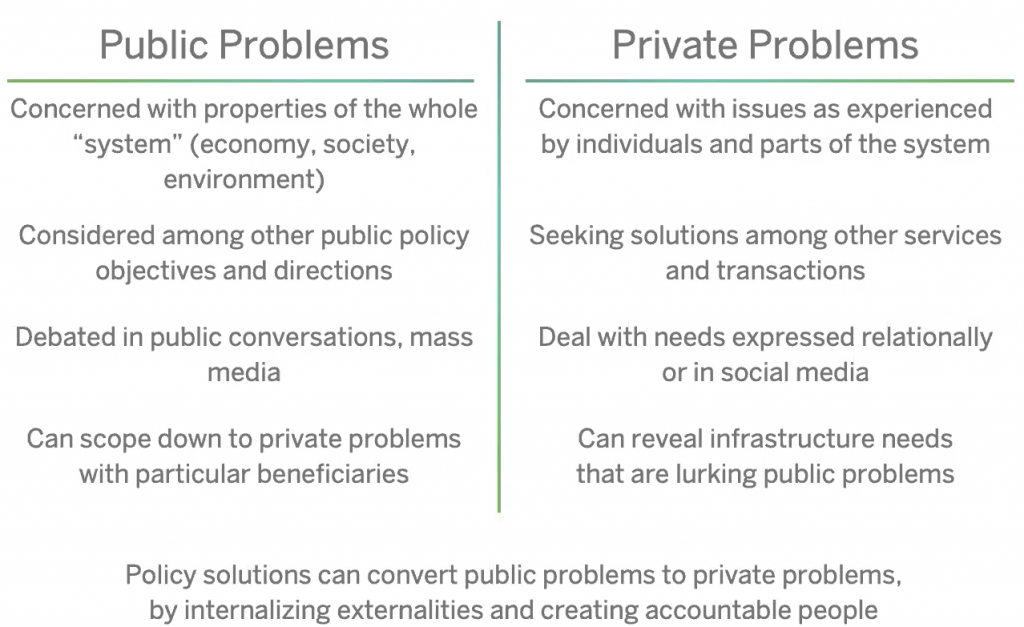

Public problems

Food waste is just one example of public problems that are concerned with the properties of the whole system, economy, society, environment.

How do we decide which public problems to pay attention to? We consider them among other public policy objectives and direction. For example, right now there’s a massive public conversation about racial inequality in the States. It is a massive public problem, something that all of us have a stake in addressing through antiracist action.

How is that public objective being positioned right now as the problem to solve, alongside managing the pandemic, handling climate change, dealing with food waste and everything else?

Public problems are chosen in the public conversations and debated in mass media. They’re part of the big larger public discourse.

Private problems

Public problems can scope down to private problems with particular beneficiaries. For any large systemic problem, there are some people in the system, whose actions really matter, and who would benefit or are harmed by it.

Private problems are concerned with issues as experienced by individuals as part of the system. If we think about a distributor in the food supply chain who has a big surplus inventory, that person experiences the food waste problem as a problem of surplus inventory. When they go to seek solutions, they’re looking for solutions to solve their inventory problem, and not a societal solution for food waste which is the broader public problem.

Private problems can reveal lurking public problems

Private problems can sometimes reveal infrastructure needs that are lurking public problems. All of us have a private problem about commuting. What do I do with myself inside the car for 45 minutes at a time? That’s created a whole market for podcasts and milkshakes, and all kinds of things. But it also is symptomatic of a larger infrastructure problem with our transportation system – that’s a public problem.

The role of policy in turning public problems into private problems – thus creating a market for corresponding solutions

Last but not least, public policy can convert public problems into private problems. So we can take something like food waste and pose a food waste ban, like we have in Boston. And now all of a sudden, it’s a restaurant’s problem to say, “I’m not allowed to throw away food waste. Somehow I have to manage this”.

So when we internalize externalities, we can suddenly take a public problem and turn it into a private problem. This is very important because if you are selling a solution to a public problem, sometimes you want to look for places where the public policy has created a market for your solution. For example: If you go to do food waste work in Boston, it’s easier to do that here than in a city that doesn’t have a food waste ban.

Three components of a good problem statement – and why people should care about a public problem

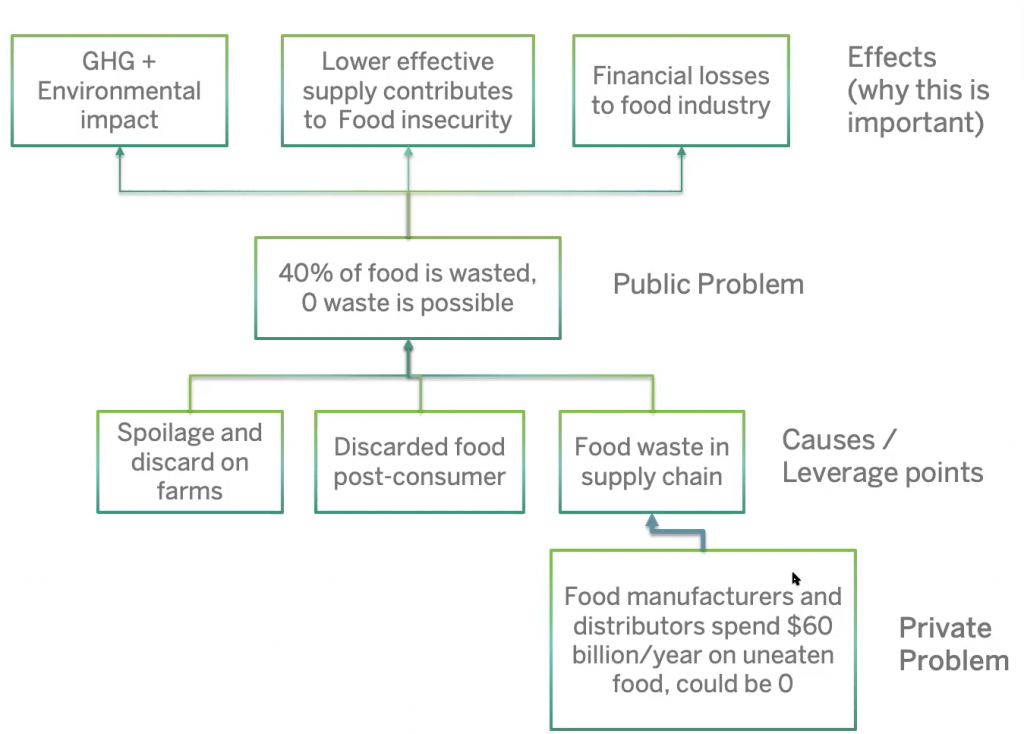

Back to Spoiler Alert. 40% of food is wasted. Zero waste is possible.

It is always useful when you’re writing a problem statement to write it as a gap between a current state and a goal state, and to quantify those as much as possible.

That distance between the current state and the goal state creates creative tension in people’s minds, just like Martin Luther King dramatizing the conditions of inequality, while saying “I have a dream”. That tension is part of what creates the narrative energy that pulls people into your story, that makes them want to be part of the conversation.

So the public problem here is 40% of food is wasted. Now sometimes you don’t need to explicitly state both sides of this. If one of them is so explicit, people just don’t like waste, we want zero waste.

There are three components to the problem statement:

- The current state

- The goal state

- Why this gap is important to close

Why is it important that 40% of food is wasted? There is a whole bunch of impact. There are greenhouse gases. There is the environmental impact of raising all those crops, all those animals, that just end up going to waste and didn’t actually produce any value for humans. There are financial losses to the food industry as a whole, including farmers. They suffer because there’s that much revenue that’s not coming in – they suffer financial losses. Having less supply contributes to food insecurity as a result of that food going to waste.

And so, all of these are reasons why we might want to care about the public problem, and all the reasons why it might pull on our heartstrings and get us thinking about why it’s a problem worth solving

Choosing a part of a complex, interrelated problem to solve

A public problem is complex. Food waste has a whole bunch of different actors in it. And so it has a lot of different causes or leverage points or facets to it.

Turns out a lot of food goes to waste on farms, or fishing boats, or other primary production sites, because there’s not good enough refrigeration, particularly in emerging markets. There’s a lot of food waste post consumer – that stuff that’s sitting in a Tupperware in the back of your fridge that you’re going to throw away tomorrow. Then there’s food waste in the supply chain, which is largely about excess inventory.

When you’re trying to connect a public problem to a private problem, you must choose one piece of the problem to go after. The one that Ricky and Emily chose to go out for Spoiler Alert was that food manufacturers and distributors in the supply chain spend about $60 billion a year on uneaten food – and that move toward zero.

Another piece of this strategy is to be intentional and explicit about what you’re not doing. Sometimes it’s useful to say what parts of the problem you’re not working on. That can even be part of your pitch. If people assume that because they’re working on food waste, that means that they’re going to deal with the funky Tupperware problem, you might have to say that’s interesting, but we’re working on a different part of it. At minimum, that strategizing is in the background of your own strategy making as a team.

And so now we’re at a private problem, because we’ve got a specific actor in the system.

Note that when we are scoping down like this, it is important to come back to the Ikigai perspective about what are we good at, and what we love. Emily came from an enterprise software sales background. And Ricky came from a management consulting background working with large companies. So, they had a disposition to work with the big food companies in the middle of the chain and to try to provide them with a B2B enterprise type solution. It fits their narrative. It’s easy to sell teammates and investors on the idea that they could help to solve that problem. So all of these things do interact.

Public sector players have private problems too

It’s important to clarify that private problems do not only occur in the private sector. In fact, sometimes private problems are held by government officials.

For example: You may be selling a service or a technology to parking meters that are able to detect whether or not a car is in the space. There is a city government buyer for that technology for whom it’s a problem. They have to keep sending their meter patrols out on a continuous basis without having any intelligence about the parking spaces. In this example, a public sector employee is experiencing a private problem and could be a buyer for a solution.

So it’s not about private sector versus public sector. It’s the fact that there’s a specific person whose job it is to solve this problem, and who has a financial incentive to try to solve it. And in this situation food manufacturers and distributors are that locus of the problem that Ricky and Emily jumped into.

Using the Problem Statement to position your enterprise

So, here’s how this problem statement ends up showing up in Spoiler Alert’s materials in 2016. If you went to their homepage of the web in 2016, what you would have seen is the customer view of their private problems in the tag line: “Surplus food happens, manage it better”.

Then there are three statements:

- “Improve your bottom line

- Empower your people

- Help your community”

This follows the classic modes of persuasion: Pathos, ethos and logos. The first statement appeals to the numbers, that’s logos. The second statement empowers your people, that’s ethos. Helping your community, that’s pathos, an appeal to your heart.

From the website you can get to an e-book that elaborates the environmental, social and financial problem of food waste the public problem. And so they do articulate that in their website and in their pitches. But you’ll notice that in a pitch, they foreground the public problem to draw everyone in, while on their website they foreground the private problem, because they are trying to sell to customers.

A template for articulating the public and private problems for an impact driven venture

For impact-driven ventures, here is a template for you to work on your problem formulation and articulate and practice talking about.

Articulate your public problem:

- What is the current state?

- What is the goal state?

- Why is this gap important to close?

Articulate your private problem:

- What is your customer’s current state?

- What is your customer’s goal state? (pain relieved, gain created)

- Why is this important enough for them to pay you?

Remember to quantify it if possible – e.g. 40% of food is wasted.

The third Axiom: Stakeholder <> Customer

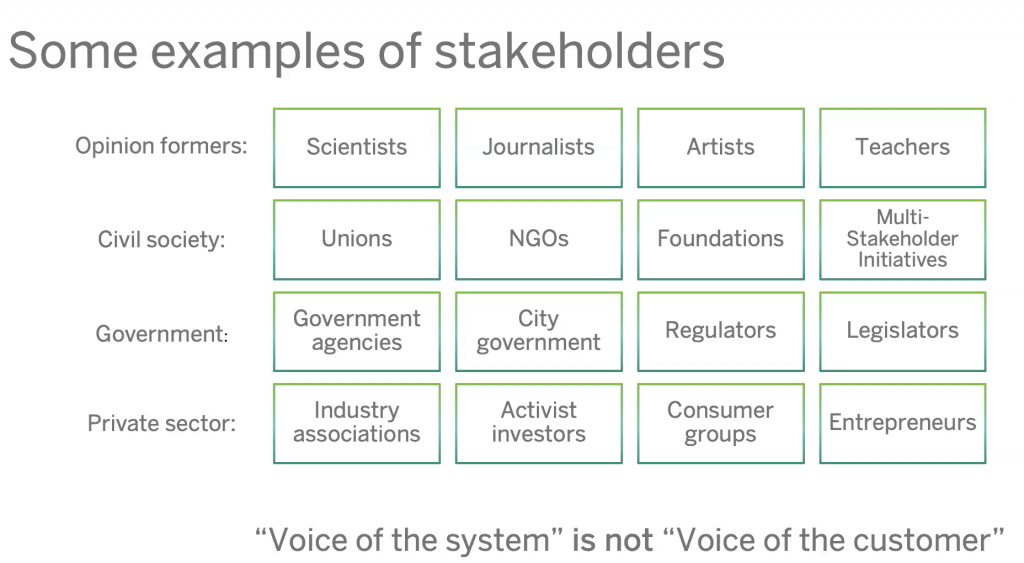

One of the things about a public problem is that public problems have a whole variety of different stakeholders, people who care about the problem.

For example, we might think about key opinion leaders, civil society, government collectives, entities in the private sector, or people on the fringes of the private sector, all of whom are thinking about this problem and might care about it.

This is very important, because these are folks who, even if they’re not going to be paying customers, might support your enterprise in various ways. They’re going to cover you with their journalism. They’re going to celebrate you at a conference. They’re going to potentially give you a grant that can help you move forward – because you’re going to be trying to solve that public problem they care about.

For Spoiler Alert, there were NGOs like the Natural Resources Defense Council NRDC that had just come out with a big report and media campaign about food waste. That made it much easier to for them to enter into any conversation about food waste, because if people had seen some NRDC publicity around it, it would confirm that, yes, this is an important thing that’s worth solving. And when the NRDC is giving talks about food waste and people say, well, what’s the solution, they can talk about Spoiler Alert and amplify the message there.

Similarly, regulators, like the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, which put in place the food waste ban here in Massachusetts, is an important stakeholder. The EPA might be talking about it, even setting rules in place that create your customers, and nudge them toward your solution. There’s a whole array of different people who might be part of your landscape.

Be careful about distractions

The cautionary story here is that all of these people are also potentially massive distractions for you on the road to raising capital, getting paying customers, securing a team, getting to market, and delivering your product.

Sometimes when you have a really good impact story, it works for attracting investors and customers and grant money. But it also works for attracting 15 different speaker invitations, all of which will take you out of the core work of building your product and getting into the market. So there is an important balancing act of trying to secure as much diverse support for what you’re doing, while also not letting it get you distracted.

Spoiler Alert completely grappled with this. Ricky was named a Forbes 30 under 30, and there was all kinds of press about food waste which included them as case examples. That was all very helpful, but it was also something that threatened to pull them in a million directions as they were trying to build their enterprise.

Mapping your stakeholders

The other important part about this stakeholder mapping is that there might be other customers who will pay you for what you’re doing, but whom you might not normally think about as being your customers.

For example, for healthcare innovations like a mitigation solution for Parkinson’s, there are a lot of different stakeholders. There’s the patient themselves. There are relatives and people who care about the patient and are concerned about them. There are care providers, which include a whole range of different clinicians from physical therapists to primary care doctors to geriatricians to attendants in an assisted living facility. There are insurers and payers who might be interested in preventative health that prevents a fall or some other more serious consequences due to tremor. Any of these people might be a paying customer. There’s always a whole array of stakeholders who are connected to that problem and are potential advocates for you.

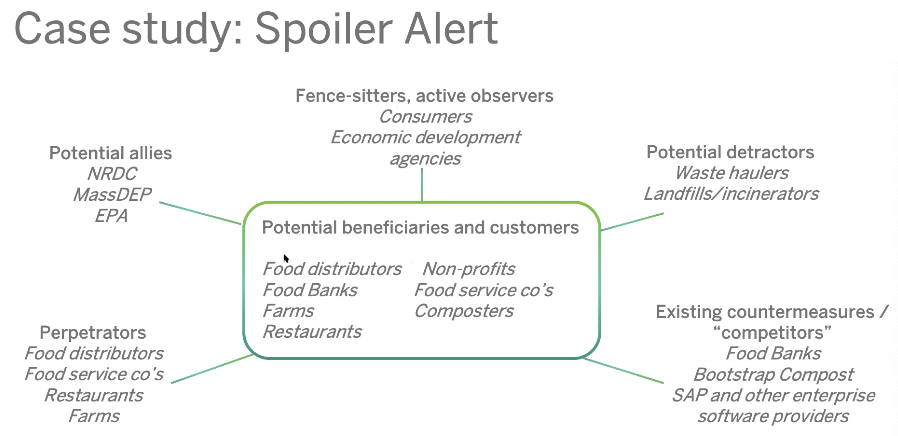

When people do a good job telling the story of the public problem and the private problem, there are always multiple characters in that story. What you need to do is to start to map out who are the characters in your story. Here is a template for doing this.

- Start with the public problem. What is the current state? What is the goal state? Why is the gap important to close?

- Now ask: Who is involved in the problem? To start, list one of each category.

- Beneficiaries: Who is harmed by the current reality? Who would benefit from a solution?

- Perpetrators and targets: Whose behavior would have to change to solve the problem?

- Allies, existing counter measures / “competitors”: Who else is working toward the goal state?

- Customers: Who cares enough about the public problem, or feels the private problem and might pay for you to close the gap?

- Detractors: Who benefits from the current reality?

- Fence sitters, active observers: Who else is connected to the problem and could be a source of insight and connection?

For the first two stakeholders: If we look at air pollution in cities, people driving trucks or cars with insufficient pollution control devices – they might be the perpetrators or targets for an effort that’s dealing with air pollution. They might be different from the beneficiaries like people with asthma, who are suffering from that air pollution.

The next category is allies. Allies and competitors actually go together very closely in a public problem because the people who also care about the problem are also trying to come up with solutions. So they are allies for you, amplifying the importance of that public problem in the discourse. But they may have other solutions. There are ways in which they’re going to be helpers and collaborators and there are ways in which they might be competing with you for attention, funding, customers, etc.

Then we’ve got customers. These are people who care enough about the public problem and feel the private problem, and might pay for you to close the gap. That is the sweet spot. That’s what we’re looking for. And so much of the entrepreneurial process is aimed at really understanding that customer relationship and getting that money in the door, which is critical and important. And the key here is to try to figure out who among this larger landscape might be those customers.

There’s a couple of other categories that are detractors – people who might oppose what you’re doing. These people may benefit from the current reality and don’t want you to solve the problem. Perhaps they have a competing product. Or who may benefit from the existing state.

Lastly, there are fence sitters and active observers who are connected to the problem or watching it. That could be a source of insight or linkage and connections to investors, customers or team members, but who are not sort of really throwing their hat into the ring.

Here is where Spoiler Alert stands in this framework.

There are perpetrators, meaning places where food waste is happening and where people were throwing stuff into the trash. That includes food distributors, food service companies, restaurants, farms across that whole value chain, there are potential allies like these government agencies and NGOs who care about the problem and might boost what you’re doing.

There are existing countermeasures, competitive people who are trying to solve the hunger problem. We’re trying to get surplus food to useful places, so food banks, small composting shops, other enterprise software providers that are trying to provide data and analytics.

There are potential detractors – people who are going to lose money. If there’s less food waste, waste haulers, landfills, perhaps incinerators, all of those are going to lose money if the food waste is transitioned over to donation or composting or some other channel. And then there’s fence sitters and active observers such as food consumers, economic development agencies. Others who are kind of watching this movie, probably care about it, but aren’t going to pay to solve it.

The potential benefits beneficiaries and customers at the center. These are all potential people who would pay for a food waste solution. And at the end of the day for Spoiler Alert, they have created a two sided solution that serves the food distributors and the food banks.

What if you are so good at solving the public problem, other players move in?

Sometimes you may be solving a problem and bringing enough awareness that your competitors start to imitate you. You want people to change their practice because they would solve your public problem. But if they did, they would be competing with you more. So there’s a funny dynamic that happens in that kind of a situation.

Seventh Generation, a green cleaning products company, is a good example. They really grappled with this because they started having really successful growth in the green cleaning space. And then the larger brands like Clorox started imitating what they were doing, and came to market with Clorox Green Works and other comparable products.

Seventh Generation had to grapple with whether this is a success or is this a failure, if they were losing market share to Clorox Green Works. From the standpoint of our social mission, our impact goals are the public problem. We are winning, because we’re changing mainstream practice. But if we’re losing customers, from the standpoint of our private problem and our private mission as a company to make revenue, we are losing market share. That’s bad.

And that tension between simultaneously solving a public problem and a private problem becomes a really big ongoing issue.

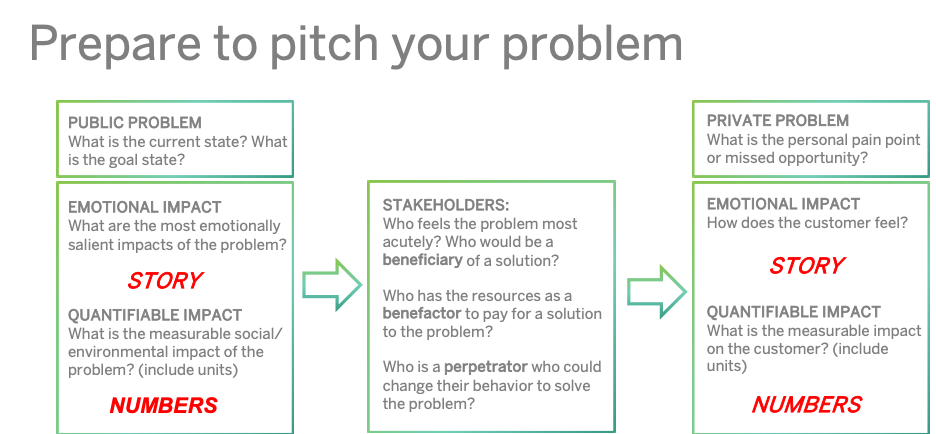

Putting everything together: Pitching the problem

Pitching your problem means being able to get up on stage or in an elevator pitch type of format and really share the full texture of your problem that you’re the problem that you’re trying to solve. This is a way to sort of broaden the audience to citizens at large, who might care about what you’re doing.

If you’re ever invited to give a TED Talk TEDx talks, you will know this. You’re not allowed to promote your product. But what you can do is promote your problem. Any onstage pitch for an enterprise is usually going to start with some sort of pitch of the problem. Following is a way to prepare.

Elements of a good impact pitch

Here are the elements that need to appear in the pitch:

- Part 1: Public problem

- The public problem: Current and goal states

- Capture the emotional impact of that public problem – the Story

- Speak to the quantifiable impact or the scale of that problem – the Numbers

- Part 2: Stakeholders

- Who feels the problem most acutely

- Who would be a beneficiary of a solution

- Whose behavior and have to change, who are the really interesting characters in the story

- Part 3: Private problem

- How do we think about that private problem from their perspective

- What’s the emotional impact

- What’s the quantifiable impact

Example: Spoiler Alert’s Techstars Boston 2016 Demo Day Pitch

Spoiler Alert’s TechStars pitch hit all the right notes. They start by saying they are “tackling two distinct but related problems: Food waste and hunger. Food is something that sustains each and every one of us”. That connects to the audience and makes everybody feel like this is something that we participate in.

“But 40% of the food produced in this country never gets eaten”. And that’s a code of current reality of a public problem that captures our imagination.

“That is $75 billion of unsold inventory and lost revenue to food businesses each and every year”. So now we have a character in our story: Food businesses. This is going to be our perpetrator and our beneficiary, a central character in the story. And we define a private problem which is explained in terms of $75 billion of unsold inventory. We have also defined a market size for any investors who are listening.

Now this is a complex story because it’s a two sided market. So now we’re going to introduce more of the picture. “There are 50 million Americans who don’t get enough to eat. And there are 50,000 nonprofits dedicated to feeding them and spending each and every day looking for more food to recover”. So now we’ve got other characters in the story: nonprofits, and Americans who don’t get enough to eat. So Americans don’t get enough to eat are a beneficiary. The nonprofits who are dedicated to feeding them are providing a countermeasure to the problem, and they are also a potential customer.

And all of this up to this point says nothing about what Spoiler Alert does. It doesn’t talk about their technology. It doesn’t talk about who they are as people. It just frames the public problem, the private problem and a couple of the key stakeholders together into a picture of the world.

And then they go from that high level problem statement to diagnose why are things the way they are. The root cause is: “Food gets wasted because there’s a giant communications gap, a lack of real time response for unsold inventory. We want to change this.”

So now we’ve got a diagnosis here. And there’s a whole array of different people who would want to join this mission, from nonprofits, journalists, government, as well as the ore stakeholders – investors, customers and team members.

And then they start talking about the solution, putting surplus inventory in our system, creating secondary markets, making collaboration efficient, dashboards and so forth.

This whole problem statement here could potentially stay the same as they go through pivots. It defines the space in which they work and who their allies might be. So this is an example of a problem pitch that follows this trajectory. It has some quantifiable impact of the larger food waste story. It has quantifiable impact of the private problem and $75 billion.

What it does not include is the story of John who works at Costco and has a truck full of watermelons that are about to spoil because it rained on the Fourth of July weekend. They have used that type of story in in longer form contexts. It doesn’t have a story about a family that is starving and food insecure and doesn’t have access to good, fresh quality produce. But you could imagine leaving those in, depending on who your audience was and how you wanted to pluck their heartstrings.

Everyone’s going to have slightly different emphasis and elements here. This is just an example of how pulling these things together really frames the importance of what you’re doing.

Pro-tip on using numbers: State the market size AND the growth rate

There is a good book titled “Factfulness” by Hans Rosling and Anna Rosling Ronnlund. One point the book makes is to tell people how much a problem accelerating. For example, the 50 million people who don’t get enough to eat – 50 may be a good number if it came down from 75 million the year before, or it may be a bad number if it went up from 25 million before. So in addition to stating the size and scale of the problem as it stands today, it would also be good to talk about the acceleration or growth of the problem and quantify it for investors. The acceleration is a signal that this is a trend that is going to get worse unless we do something now.

Q & A

Q: Do you always need all these elements of story and numbers, public and private problem?

No. Sometimes the problem pitch can be a lot simpler, if the beneficiary and end user are the same person, and they are part of a population that everyone recognizes as vulnerable and underserved. Many health innovations have this character. All you have to do is tell the story of a person – e.g. the Parkinson’s patient at risk for a fall, or burning themselves, and then back out to the number of people who face that risk, framing that population as a shared public problem we all have responsibility to solve. Of course there are more characters in this story as described above, and they may come out in the nuances of your marketing, distribution, and payment model. But the problem pitch might be simpler.

Q: How important is it to be convincing that your solution to the problem is a good one, as opposed to the problem itself is a good one? For example, perhaps food gets wasted because it spoils en route. Is it important to even mention while you’re targeting this and not an adjacent problem?

When we think about a problem, we can break it down in a lot of different ways. They’re choosing to work on this part of this branch of the tree. They could be at a conference about food industry innovation, they’re on a panel about food waste and they’ve got one company that’s working on refrigeration trucks, another that’s working on refrigerator management software and one that’s working on surplus inventory. In that situation you might have to have a little competitive conversation about which of these is worth investing in. But the reality is that that’s rarely useful.

It’s most often useful to say: “This is a big, complex public problem. We need all hands on deck to help us try to solve this. I love seeing my colleagues here working on these other branches of the problem. We’ve decided to focus our attention on this unsold inventory. For me, that really became clear when I went to this Costco and I saw this container full of watermelons that were rotting, because it rained on the Fourth of July weekend. And now I really can see this as something where we can attack the problem. We have distinctive capabilities on this because we’re enterprise software people. And so we knew how to sell to big businesses, we can make a difference with the resources and capabilities that we have.”

So there’s a way of being both confident in your own capabilities, humble about working on a small size of the system, and confident about the importance of the bigger picture problem to work on.

Also, you have to know your audience and the format of your pitch. If this is a one minute pitch, you might not even want to get too much into your solution other than convincing them that you are the team to be the ones solving the problem. If you’re talking about a 10 minute talk or a 30 minute investor pitch one on one, that’s where you really need to go into the details, without going too deep. If you are in a three hour due diligence deep dive with their tech team, you have to go deep on it.

So really, this is a question of knowing your audience and what do you need to convey, at what stage of a conversation to get to the deal, or the goal you are trying to achieve.