Project Description

Master Classes are deep dives into venture creation by MIT ecosystem thought leaders. Browse all Master Classes Here.

This masterclass on pricing is based on notes taken during an interactive workshop by Professor Catherine Tucker, the Sloan Distinguished Professor of Management and a Professor of Marketing at MIT Sloan. She is also Chair of the MIT Sloan PhD Program.

Value based pricing

The first thing to know about pricing is that we should do value-based pricing. Value-based pricing is a strategy where prices are based mostly on the customer’s perceived value of the product or service. This works well when the customer is fully informed about the product and competitor products.

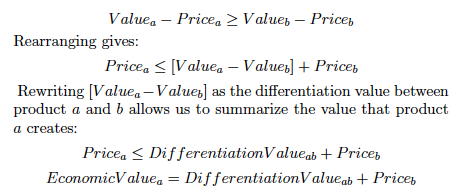

We use a well-established framework called “Economic value to the customer” or EVC to understand the value we can create for the customer. The EVC is based on the insight that a customer will buy a product only if its value to them outweighs the value of the closest alternative – or when Utility (a) is greater than Utility (b). The utility of a product depends on its value to the customer minus its price.

Therefore, to sell a product, a firm needs to price at or below its competitor’s price plus the value advantage its product has to the customer over the rival product.

Note that this works well when there is a “next best thing”. But if the next best thing is death or extreme discomfort, as in the case of a life-saving drug, this messaging doesn’t work.

The other thing to know is that oftentimes we do have a choice in terms of a pricing decision. We don’t have a fixed amount of value we need to extract for a fixed amount of value we can deliver. For example, in the case of a medical device, one could dial up and down the functionality and change the price accordingly. One could start with a premium priced version that offers a wide range of functionally that delivers a large amount of value. Then over time, we can release a lower priced version that offers a portion of that value.

The first question: Pricing architecture, not the dollar amount

The most useful way to go when working with customers on pricing will be finding out how to price it. Is there a world where the customers will be happier with a subscription? Is there a world where they are happier if the pricing is more transparent?

The more we can have the conversation about the packaging of the price, and the more we can take away from the actual price, the better off we are.

Therefore, we should stop worrying about $8 or $12. That is not the right first question. The right first question is: “What is going to be my pricing architecture?”

The pricing architecture describes the who, what and how often you are planning to price. You can see why this is very important even in product design. The “how often” will drive what you are making – is it disposable? Once you work out these different aspects – it will help with product design.

On recurring revenue – a good match if the customer sees more value in Month 4 than in Month 1

Often, a lot of startups are tempted by recurring revenue. It is tempting, because it excites VCs and helps you build the business.

The problem is that some products and services are not well suited to a recurring revenue model. Therefore we need to have a mental model: Does the product have more or less value in month 1 or month 4?

If the product delivers more value in Month 1 – if most of the value is delivered up front – you will waste a lot of time and money trying to create a recurring revenue model. A subscription model will be hard to achieve if the value truly slopes downward over time.

When the customer complains about the price compared with commodity pricing from their competitors

The first thing to know is that the customer complaining about the price is actually a good thing. If they do not complain, that’s a problem.

One mistake that startups make is listening to their customers too much. We are taught that we should talk to customers about everything. That is true – except where it comes to pricing. Customers are astonishingly dreadful about being straightforward about price.

The way we experience prices as a customer is that you see a price, and you take it or you don’t. When you ask customers about prices you don’t get good data.

The better way to test pricing is to put the price in front of them, and see if they will do something about it.

Techniques for testing pricing

The good news is that there is a set of techniques to ask pricing questions. You ask this question in a specific style.

No one asks these questions unguided. You do not say: “How much will you pay for this product”. Instead you come to a website you see the product priced at a certain amount. Do they convert, or do they go out and search for an alternative? Then you randomize the amount people see so some people come to this website and see one number, another sees another. This helps you trace out the demand curve.

When you do a survey in which you ask: “How much will you pay?”, “What are you willing to pay?” – that data is garbage. You have to set up an A/B test instead.

Q&A

What strategies are good for testing pricing if it is a medical device?

Typically with medical devices, money is not made through the pricing model, but through the pricing architecture. Being innovative and thoughtful about that makes the difference.

For example, you may price an input to a device, and you end up having a monthly model instead of making money off of the device.

Medical devices are regulated. You can try to do value based pricing, but the pricing architecture can give you a lot of options.

How do we socialize a value-based, performance-based fee structure to an enterprise customer when this is a new pricing architecture and customers don’t have a pre-existing budget category for it?

The price is directly tied to value and that is great. That said, one should think about how to solve for the feedback. When you are starting out and you are testing a new pricing architecture, it will be difficult. But don’t give up.

Let’s say you are selling to a big company. The company says, we don’t know what budget to use for this and we cannot pay the fees you specify. You could go in and say, we will take a smaller fee, but in return we want your data. You can negotiate other margins in the first year. Then they can use the data to make the offering much more valuable and then increase the fees in year 2 and beyond.

Do we need to worry about the taxi meter effect if we have a metered model where customers are charged based on their utilization of our service?

The taxi meter effect is when you try to be transparent by telling them at all times how much they are paying – and that transparency backfires. The customer reacts by looking at the meter and it is awkward and you get angry when you are in traffic.

However, you don’t need to worry about that when you are doing B2B enterprise models. It is a metered model – but they get a bill at the end of the month. As long as you do not make a dashboard so they can see the price go up and up every minute you should be fine. Just invoice them each month.

That said, you need to be ready to be firm in that they will look for caps and bands. If you want to do a metered model you need to resist caps and bands in the beginning.

Is it better to charge a percentage fee or a monthly subscription for a consumer based FinTech service that helps consumers buy assets and build a portfolio?

In FinTech the actual pricing model for assets and products are all 10 or 20 years old. They will have a lot of anchoring about what a pricing architecture looks like.

Any time you have a subscription model, there needs to be a strong case that in 6 months, you get more value than in Month 1. There needs to be a strong case for switching costs. There needs to be a personalization story or network effects or some such.

The second thing to know is that it is fine not taking the percentage fee. The aim for a consumer based FinTech model is to make a lot of money in year 5. You will not make so much money in Year 1 – but you will make money when you grow.

For an IoT device with a hardware component, we are collecting data – what do you think of a subscription model?

In general, it is a struggle in that kind of a wearable market to charge a subscription fee or a high enough price. This is because there has been a lot of anchoring for a lot of wearables. People will think what’s fair is lower.

What to do about this? How to handle the cost of goods sold (COGS)?

We try to ignore cost as much as possible in pricing because the right question is always, how will the pricing level I set and the implied demand affect my costs?

There is an assumption that there is a fixed COGS for a product. But if you price it high and you sell X units, the cost will be different if you price it low and you sell Y units and Y is a lot bigger than X.

As a first order thing, if you shift your price upwards or downwards, the amount of the output shifts, how does that affect your cost? If the cost is constant then you have a situation of price high – because there is no possibility of the cost going down.

The issue is where will the economies of scale kick in. That should be the only way one thinks about cost. It could be that there are some products with lumpy pricing thresholds. Coffee makers – the demand curve completely shifts at $99. Above that – premium products. Below that – commodity products. You need to figure out whether your product has a lumpiness in the demand curve. Is there a discontinuity?

How do you think about b2b enterprise businesses where there are very few potential customers (500 or less)? Should we do up front fees or a subscription?

If you have only 10 potential customers, you are limited. For 500 – half of them may just want to pay up front. The other half may be willing to do a subscription. If it works out – stick with licensing and don’t worry that there is a portion of the market that will be a harder sell.

What about performance based pricing in an enterprise setting?

It is a wonderful idea but it is difficult to sell to companies. It is easy to sell performance based pricing when both firms see themselves as equal contributors. However if it is a new venture or startup, the client may not see the new venture as an equal. There will be certain established firms or processes which will not adopt. That is a problem. Ultimately you will make a few sales in the beginning and then validate the pricing model.

What should we think about regarding the complexity of pricing models where you mix and match pricing architectures?

Complexity is difficult. You can design a pricing architecture that matches the value. But if you pursue it you need to figure out how to fund that and how to fund the company in the beginning.

Are there pricing architectures for medical devices that are more successful than others?

The best examples are in the consumer market. Let’s say you are making a medical testing device that uses paper strips. It is tedious if you run out of strips. She did something coles to the dollar shave club and got rid of the taxi meter effect. They priced a fixed mount and got rid of that.

There may be more examples in direct-to-consumer medical devices where you can draw more inspiration.

What if we implement a rental model, but people stop paying and keep using the product or service because it is still in their possession?

The Keurig coffee maker is a great case. They started off – their model is that they subsidize the brewer and they make money off the pods. Initially they did poorly because they sold the coffee makers but not the pods. They decided to sell to the newly wed market. When you are newly wed, you put up a big list and people buy it. But the issue is they have the brewer and they did not want to buy the expensive pods.

It’s all about targeting. Your job is that your targeting is so spot on that you nullify that risk. If you target customers where value is improving over time you don’t run the risk. It is solvable but you cannot sell it to “anyone” – only to a tight target.